Revolutionary advancements in research have shone a spotlight on previously unknown factors that may have led to the demise of Neanderthals, our ancient human relatives. These insights stem from a detailed examination of the genetic material of one of the last remaining Neanderthals.

Deciphering History from Genes

The debate over the true age of Neanderthal remains found in southeastern France has been a contentious issue among archaeologists and geneticists since its discovery in 2015. The remains, named “Thorin,” were initially thought to be either 50,000 to 42,000 years old or near 100,000 years old based on contrasting DNA analysis. A thorough evaluation of Thorin’s genetics placed him within a previously unidentified Neanderthal lineage that diverged from their ancestors approximately 103,000 years ago.

This revelation overturned the assumption that all Neanderthals came from a homogenous population. Archaeologist Ludovic Slimak, the principal investigator of the study published in Cell Genomics, remarked, “When the geneticists re-evaluated their methods, they had to overhaul our entire understanding of Neanderthals.” This refocusing on genetic data could resolve conflicts about Thorin’s age and suggest a period of isolation that had not been identified before.

Cultural Patterns and the Path to Oblivion

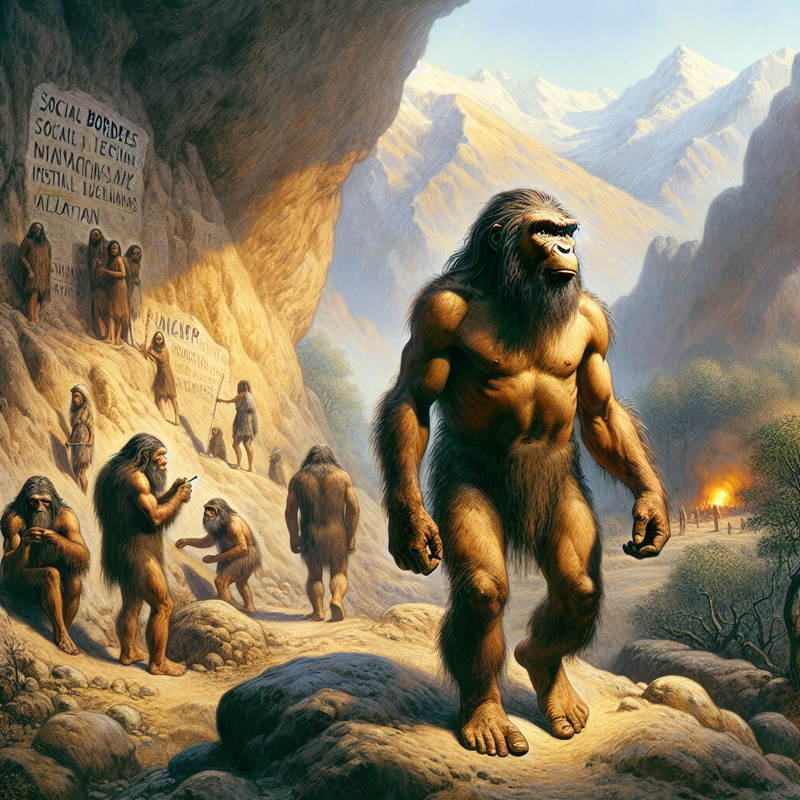

Research shows that Thorin’s community likely lived in prolonged genetic and cultural seclusion, enduring over 50,000 years. Such isolation could have resulted in intense inbreeding, depleting their genetic pool, making them more vulnerable to diseases, genetic defects, and changes in their environment. Thorin’s group represented only a small segment of the overall Neanderthal populace, yet their isolated way of life sheds light on the larger question of Neanderthal disappearance.

It appears that Thorin’s group deliberately chose seclusion even though they were not geographically isolated from other Neanderthal groups. Slimak explains that they encountered “a social border,” emphasizing the impact of social and cultural divisions on the Neanderthals’ eventual extinction.

Meanwhile, contemporary humans from that era formed broad, intermingling societies, often mating with various populations across a larger landscape. This adaptive social strategy likely contributed significantly to modern humans’ ability to endure and thrive during difficult times.

Paleolithic archaeologist April Nowell, who was not involved with the study, mused on the significance of these findings, suggesting, “The genetic isolation is pointing us towards intriguing aspects about Neanderthal populations, their struggles and their ultimate fade-out.”

As investigations progress, the unraveling of Thorin’s DNA narrative provides a moving perspective on the intricate tapestry of human evolution and the elements underlying extinction.