The Field of Paleoanthropology Shaken by Turkish Fossil Findings

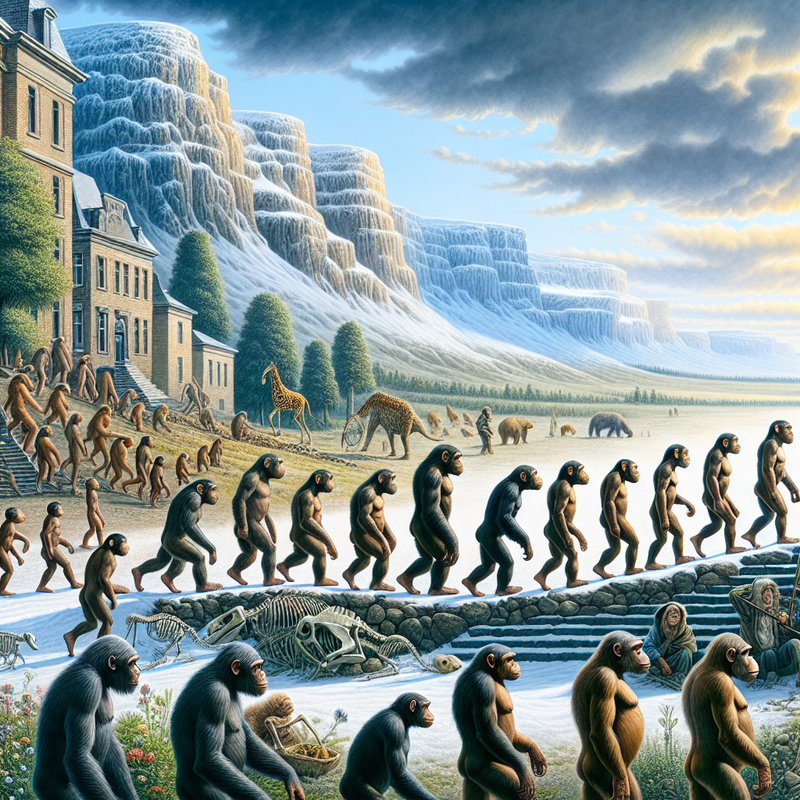

A transformative discovery in Turkey has shifted the paleoanthropological landscape, offering evidentiary support that our ancient human relatives—known as hominines—may have their evolutionary roots in Europe, not Africa. Central to this revelation is a fossil identified as Anadoluvius turkae, an extinct ape species presenting a credible argument against the traditional belief that human evolution began exclusively on the African continent.

Contemplating a New Genesis for Humankind

For decades, Africa was recognized as the birthplace of mankind, the location where our earliest hominine ancestors were thought to have evolved. However, this paradigm is now being questioned following the unearthing of the Anadoluvius turkae fossil, bearing an age of roughly 8.7 million years, at a paleontological site known as Çorakyerler, situated in the proximity of the city of Çankırı in Turkey. The discovery hints at a potential European chapter in the evolutionary narrative, suggesting an origin and subsequent migration pattern for hominines from Europe to Africa.

This hypothesis has gained traction thanks to the work of researchers such as Professor David Begun of the University of Toronto. They meticulously examined the nearly intact skull, revealing anatomic characteristics distinctive to hominines. Traits found in Anadoluvius reflect similarities with other known eastern Mediterranean ape species such as Ouranopithecus and Graecopithecus.

Professor Begun commented on their findings: “The fossil’s completeness allowed for a more comprehensive and nuanced anatomical comparison. Remarkably, most of the facial structure is preserved, enabling us to use mirror imaging to reconstruct it. What is groundbreaking is the preservation of the frontal bone, extending to the top of the head.”

Revelations from a Diverse Mediterranean Ecology

The existence of Anadoluvius turkae exemplifies the rich biodiversity of the Mediterranean during the late Miocene period, illustrating that the region was more of an evolutionary junction rather than a secluded haven for a singular hominine species. As such, the eastern Mediterranean could have functioned as an essential ecological passageway between the continents of Europe and Asia.

Moreover, the environment these early hominines inhabited is reflected in the fossil’s morphology. Evidently, Anadoluvius and its related species appeared to be adapted for life on the ground rather than in the trees, indicative of their adaptation to the dry, open landscapes prevalent at the time.

Shifting Environments and Emergence of a Paradigm Shift

Environmental alterations in the late Miocene, particularly the contraction of forested areas and the spread of grasslands, seem to have been influential in the adaptive trajectory of hominines. These changing landscapes could have spurred migrations into Africa where they ultimately gave rise to subsequent species.

“This newfound evidence lends weight to the idea that hominines may have geographically originated in Europe before migrating to Africa along with myriad other mammalian species between nine and seven million years ago,” elaborated Begun. “However, conclusively proving this requires additional fossils from both Europe and Africa, dating from eight to seven million years ago, to clearly delineate the connections between the regions.”

The recovery of Anadoluvius turkae not only invites a thorough reassessment of the temporal and geographic aspects of human evolution but also serves as a testament to the ever-evolving nature of scientific discovery.